Saudi Arabia helped us win the First Cold War. It's not this time.

The China-Russia axis is winning new friends

During the First Cold War, Saudi Arabia played a key role in bringing the Soviet Union down by boosting its own oil production so much in the 1980s that the price collapsed. During this Second Cold War, though, it’s seemed to switch sides to the extent that it’s helping prop Russia up by slashing its output right now.

This is how alliances end. Not with a bang, but an unanswered phone call and a half-hearted fist bump.

Now, as far as deals go, the one we have with Saudi Arabia is pretty straightforward: we protect them, and they pump more oil when we need them to. The best example of this, as we just mentioned, being when the Saudis, with what was almost certainly plenty of American encouragement, launched a price war in 1986 that helped push the oil-dependent Soviets into bankruptcy. It was the last in a series of fiscal shocks that ended up bringing the 45-year standoff between the world’s two nuclear superpowers to an end for the almost farcical reason that the Soviets couldn’t agree on how to balance their budget. Never before had so much been decided by so little.

This was the irony of the Soviet system: left-wing central planning depended, to a large degree, on right-wing macroeconomic policy. Why was that? Because inflation was communism’s Achilles heel. One of the many problems with having the government decide prices instead of the market was that officials almost never felt like they could increase them when they needed to—and with good reason. Soviet leaders well remembered that higher food prices back in 1962 had set off riots in the southern city of Novocherkassk, which, when the first troops on the scene had refused to fire on the crowds, had seemed like a potentially revolutionary moment. (It didn’t end up being one, though, because the Kremlin was quickly able to find more reliable soldiers who were, in fact, willing to shoot civilians).1 And in case they did manage to forget any of this, Poland was there to remind them. Its communist government had had to resort to declaring martial law in 1981 after its own ill-fated food price hikes had generated such massive opposition, led by the new trade union Solidarity, that the very survival of the regime had been called into question. Raising prices was a dangerous business for Marxist-Leninists.

And so they didn’t. Instead, the Soviets tended to keep the prices of goods below what it cost to actually make them, which worked about as well—not very—as Econ 101 would have told you. Even communism couldn’t change the fact that people don’t like to sell things for a loss, and would rather not sell anything at all if you try to force them to. The predictable results were constant shortages and long lines. And the only reason it wasn’t even worse than that was that the government tried to make sure stores at least had something on their shelves by buying high and selling low to supply them itself. In other words, it would pay what the price should have been so that shops could charge far less.

There was a manageable dreariness to all this, with things being annoyingly difficult but not impossible to find, as long as deficits weren’t big and inflation wasn’t high. But what if they were? Well, in that case, the cost of making goods would go up, but the price you were allowed to sell them at wouldn’t, so companies would have even less incentive to produce things and the government would have to spend even more to subsidize them. This would make stores go from being partially full to completely empty—which, of course, is exactly what ended up happening.

The road to bankruptcy

It started, as we said before, with what were some pretty run-of-the-mill budget problems. The big picture was that the Soviets had a lot of spending they didn’t feel like they could cut, and a lot of revenue they didn’t really have a way to replace—but suddenly needed to. Although this wasn’t just a matter of dollars and cents (or rubles and kopeks, as the case may be). There was a moral dimension to it as well. The reason the Soviets didn’t think they could politically afford to get rid of spending they couldn’t financially afford anymore was that the state had lost the ability to inspire loyalty any other way than buying it. The revolutionary zeal, and accompanying terror, of 1917 was long since gone; so too was the patriotic fervor, born of a fight for survival, of 1941; all that was left by the 1980s was the desiccated husk of the old beliefs, the faith in dialectical materialism replaced by actual materialism, a selfish cynicism the new de facto ideology. Seen in this light, the Kremlin’s food subsidies were the price of maintaining the masses’ acquiescence; its military spending the price of keeping the generals from moving against it, and, from 1985 on, its investment binge the price of getting party elites to go along with new-Premier Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempts to reform the economy. That didn’t leave much spending for them to cut.

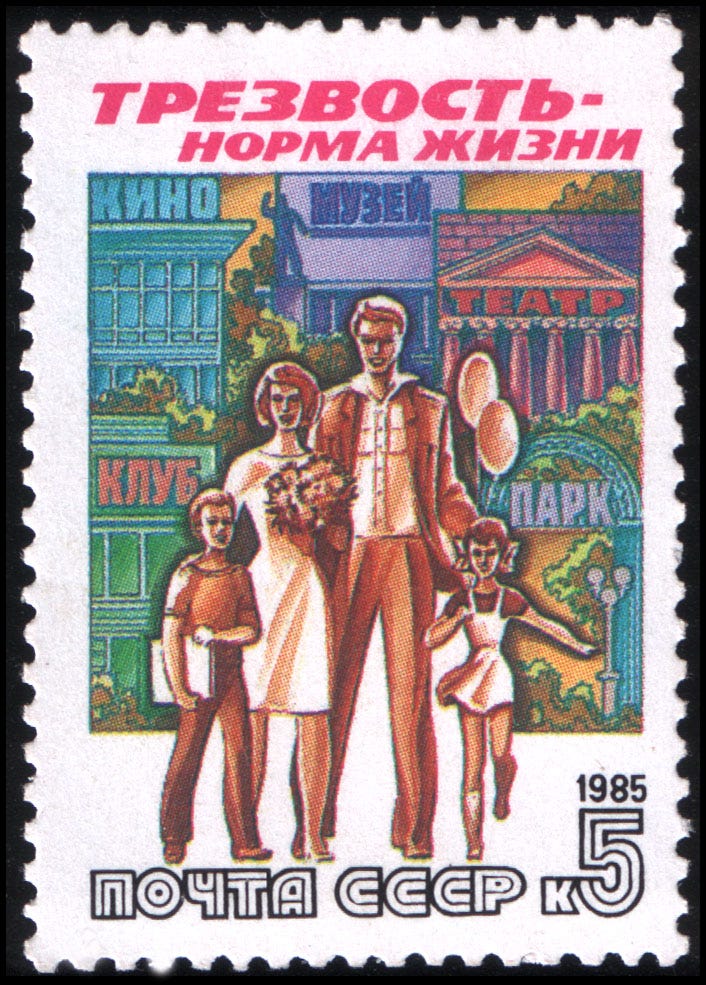

But they needed to. That’s because of the way the USSR started hemorrhaging money in the mid-1980s. There were two main culprits here. The first was such an absurd example of unintended consequences that it almost seemed like a satire of the sickness of Soviet society. That was the budget hole that Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign created. Russia, it goes without saying, had had an intemperate relationship with vodka long before the Bolsheviks ever came to power, but it still managed to reach new levels of excessiveness under the Soviet system where, as the old joke went, people pretended to work and the bosses pretended to pay them. Why show up sober, or even at all, when how good a job they did was irrelevant? They didn’t. Instead, alcohol consumption doubled on a per capita basis between 1955 and 1979, which, in turn, was to blame for 90 percent of the days that Soviet workers missed.2 So Gorbachev, like the good technocrat he was (or at least aspired to be), tried to sharply curtail the sale of booze. And in this he was successful, although the benefits weren’t as large as he might have hoped given that many people just switched over to moonshine, and the costs, in terms of lost revenue from alcohol taxes, were larger than he might have expected; they amounted to 1.3 percent of GDP.3 Soviet communism, like tsarist autocracy before it, relied to an embarrassing degree on taxing the drunkenness it encouraged.

As painful as this was, it wouldn’t have been anywhere near enough to even cause a downturn in the economy, let alone the downfall of the Soviet empire, if another shock hadn’t come along at the same time. That, as we said at the start, was Saudi Arabia’s decision to triple its oil production in 1986. Prices, by that point, had already come down a substantial amount from their post-Iranian Revolution highs, but this sent them into a free fall; oil went from $30 to $10-a-barrel in a matter of months. This cost the USSR, which was just as much a petrostate then as Russia is now, another 1.3 percent of GDP worth of revenue, just like its anti-alcohol drive had.4 It’s important to keep in mind, though, that even this shouldn’t have been anywhere near enough to cause the problems that it did. Losing this money, after all, only brought the USSR’s budget deficit to 6 percent of GDP5; countries manage that kind of situation all the time. But the Soviets weren’t able to because every normal option—cutting spending, raising taxes, or just admitting how much more they needed to borrow—seemed too unpopular to leaders who were acutely aware of how tenuous their hold on power was. They preferred to take the path of least fiscal resistance, which, in rather short order, proved to be the most economically expensive one. That was simply printing the money they needed.

It didn’t take long for inflation to take off. Now, on the one hand, it’s hard to say just how high it got when price controls made the official numbers fairly meaningless, and black markets weren’t exactly keeping records. But, on the other, it’s easy to see that it was more than high enough to make society fall apart. The most immediate consequence of which, as we touched on before, was that stores started running out of things entirely.

In the end, Engels was right that communism would lead to the withering away of the state

This was especially a problem when it came to food. Which, it’s worth taking a moment to point out, really shouldn’t have been the case. The fertile black soil of Ukraine had long been the breadbasket of Europe; if there’s one thing the USSR should have been able to do, it was feed itself. But the fact of the matter, in what might have been the biggest indictment there was of Soviet economic management, was that the lands of the USSR had gone from being the world’s biggest grain exporters under the tsar in 1913 to the world’s biggest grain importers under the communists in the 1980s.6 That’s how inefficient their collective farms were. (The few private farms that were allowed to exist into the 1960s were so much better run that, at the time, they accounted for over 33 percent of the USSR’s agricultural output despite only using 3 percent of the cultivated land).7

This low level of productivity would seem like the good old days, however, once prices started soaring like they did in the late 1980s. State-run farms, which had always suffered from a lack of motivation, now had even less of it since all this inflation meant they’d have to sell their crops for less and less of what they really cost; official grain harvests slumped from an already anemic average of 200 million tons a year during the second half of the 1980s to a mere 60 million tons by 1991 (although, to be fair, some of this was due to more grain being siphoned off to the black market).8 But in any case, this meant that the Kremlin had to buy more food overseas to then sell at deep discounts back home, which wasn’t easy, or eventually even possible, for the hard currency-strapped Soviet state. Not that Moscow didn’t try; by 1988, just when things were really beginning to spin out of control, it was already spending 5 percent of GDP on meat and dairy subsidie alone.9 Even if that’d been sustainable—which it wasn’t—the bigger problem was that it didn’t do much good to help people afford things that were so hard to find in the first place. Lines had actually gotten so long by this point that, according to one Soviet economist’s calculations, people could have earned 75 percent of the average income if they’d spent that time working instead.10 In the world of the eight-hour Soviet workday, shopping had become like an extra nine-to-three job. At least, that is, until things deteriorated so much, like they did in 1991, that only 8 percent of markets had butter, 12 percent had sausages, and 48 percent didn’t have anything at all.11 Waiting for groceries had turned into waiting for Godot.

In the end, Friedrich Engels was right that communism would lead to the withering away of the state. It was just wasn’t for the reason he thought it would be. Instead of creating a classless society where the government wasn’t needed, communism had produced so much privation that the regime wasn’t wanted. It was so unloved, in fact, that it faced what amounted to three separate revolutions by the end of the 1980s. The first was Gorbachev’s failed revolution from above, the second was workers’ nascent revolution from below, and the third was regional party bosses’ ultimately successful revolution from within. Initially, despite some unrest in the Baltics and Caucasuses, it seemed like it was just going to be a contest between these first two: could the government change itself before the people wanted to change the government? Gorbachev, for his part, did manage to push through some major economic reforms, including allowing large-scale private farming, but was never able to balance the budget like he needed to. That would have required big cuts to either consumer subsidies or the military, the latter of which, Gorbachev only belatedly learned, made up about 40 percent of total spending.12 This might have been an understandable failure—it wouldn’t have been easy to take money from the people at large or the people with the guns—but it was a failure nonetheless. It meant that the government had to keep printing money, that inflation kept getting worse, and, most importantly, that the workers kept becoming more desperate. By the spring of 1989, this dissatisfaction had grown so severe that many of the Party’s preferred candidates lost in what were the country’s first semi-free elections in more than 70 years13; by the summer, it erupted yet again when coal miners launched a nationwide strike against their disintegrating standards of living; things didn’t get any better in the fall or winter, either; they were all seasons of discontent now.

But despite all of this, there wasn’t so much a national opposition as there were national oppositions (which, at least in the case of Armenia and Azerbaijan, could be very much at odds with each other). Whether they were genuine nationalists, like in Tblisi or Vilnius or Yerevan, or more opportunistic satraps, like in Almaty or Bishkek or Tashkent, local leaders started to realize that the path to power was no longer mouthing Marxist-Leninist pieties, but rather speaking up for their people—and, more to the point, that Moscow couldn’t stop them from doing so amidst all the economic chaos. Practically-speaking, this meant that some of them stopped sending the taxes they collected back to the Kremlin, so that by 1991 it was only receiving 60 percent of the money it expected from them.14 This, in turn, helped send the deficit from, what was under the circumstances, an already-dangerous 10 percent of GDP to an all-but-fatal 30 percent over the span of a single year.15 Unable to borrow anymore even if it’d been willing, and unwilling to cut spending even though it was able, the USSR was forced to print even more money, setting the stage for hyperinflation in its soon-to-be successor states. (Inflation hit triple digits in almost all of the post-Soviet republics, with Armenia leading the way at over 430 percent).16 The Party’s half-hearted efforts to use the army to stamp out this separatism failed in Georgia in April 1989, Azerbaijan in January 1990, and Lithuania in January 1991; KGB and military hard-liners’ half-baked coup attempt was no more successful at reviving the authority of the state in August 1991. As far as the Soviet Union was concerned, the centrifugal force of economic collapse had become stronger than the centripetal force of repressive violence. All that was left to do was to make the divorce official.

With friends like these…

Things are very different this time around, though, at least when it comes to Saudi Arabia’s role. Far from undercutting Russia’s finances when we’ve needed it to, it’s actually gone out of its way to support them right now. In particular, it’s gotten OPEC to strike more deals with Russia on cutting their combined oil production, now by a total of four and a half million barrels a day, in a bid to prop prices up. These are the actions of an ally, just not ours.

Why has Saudi Arabia switched sides even if it would like to pretend it hasn’t? The easy, and not entirely wrong, answer is Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. He is apparently a sensitive soul who dislikes being called a murderer just because the evidence overwhelmingly points to him ordering the, well, murder of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi. The economic consequences of this thin skin, then, might be that MBS is more inclined to try to keep gas prices high to harm the political prospects of President Biden, who has criticized him in the strongest possible terms, and help those of former President Trump, whose family has received billions from the Saudis in what is one of the more brazen examples of corruption you’ll find. It’s great power politics as a function of personal pique.

But this doesn’t explain why our other oil-producing allies in the Middle East, like the United Arab Emirates, have also stood with Russia since the start of the war. Something else must be going on other than MBS’s hurt feelings. Something like a revolution in global energy markets. The point being that neither Saudi Arabia nor the Gulf States have ever increased oil production solely because it was in our interests, but only when it was—at least somewhat—in theirs as well. Those two things just used to coincide enough for our alliance with them to make sense. In the 1980s, for example, the Saudis were willing to push prices down because, in the short-term, it allowed them to regain market share from higher-cost competitors like the Soviets, and, in the longer-term, it helped them hold on to that market by making it seem less urgent for customers like us to develop lower-cost alternatives.

This calculus has been flipped on its head, however, by the rise of shale oil, the fall of communist ideology, and the advance of electric vehicles. In the last decade, the biggest threat to OPEC’s Middle Eastern-based hegemony over the oil market hasn’t come from Siberian wells, but rather North Dakotan ones opened up by new shale drilling; Russia, in the meantime, had already started looking less menacing to these Arab petrostates once it had given up the messianic atheism of its Soviet days; which, especially with electric vehicles beginning to break into the mainstream, meant that the Russians, Saudis, and Emirates had suddenly become natural partners. Their economic rivalry was subsiding and their opposing worldviews were reconciling, leaving only a shared desire to push out American supply so that they could push up prices as much as overall demand would allow in however much time oil has left as the lifeblood of the global economy. This is how we went, in the course of just 10 years, from a world where Saudi Arabia sold oil to us and competed with Russia to one where it competes with us and, taking advantage of sanctions-depressed prices, is buying oil from Russia for its power plants.

But it’s not just economics that’s driven a wedge between us and the Saudis. It’s geopolitics too. Just like we have our Cold War with Russia, Saudi Arabia has had its own with Iran. This has primarily taken the form of a series of sectarian conflicts between Saudi-backed Sunnis and Iranian-backed Shias, with the battleground shifting from Iraq over to Syria down to Lebanon and even as far south as Yemen, the last of which has been of particular interest to Saudi Arabia (and its vulnerable oil fields) next door. The issue is that, while we’ve been happy to help the Saudis counter Iranian influence for a long time now, we’ve begun to lose enthusiasm for it more recently. Part of it is that Saudi Arabia’s air campaign against Yemen, which has only been possible thanks to American-made weapons of war, has been brutal beyond anything they can justify militarily or we can morally. But the larger portion is that, at least when it comes to Democratic administrations, we’ve realized that Iran is an enemy we can’t afford so much enmity with. Between the rise of China, the aggression of Russia, and, above all, the complete quagmire of Iraq, it’s become clear that we have neither the time to focus so much on the Middle East nor the ability to change it all that much even if we do. We have no choice but to talk to Iran. That’s too chilly a war, if you can still call it that, for Saudi Arabia’s tastes—to the point that it’s decided it’d rather get China’s help to not fight Iran if it can’t get ours to fight it.

New Cold War, same as the old Cold War?

The hardest question to answer here is also the most important: how does all this end? On the one hand, Putin’s Russia has far narrower ambitions than Stalin’s (or even Brezhnev’s) Soviet Union ever did. Tsarist revanchism has replaced worldwide revolution as the order of the day. So it’s possible to imagine that this conflict will be contained; a bloody but ultimately limited battle in the borderlands between a Fukuyamian Europe and the Hobbesian world at-large, much as was the case, albeit on a smaller scale, the first time Russia tried to split the Donbas off from Ukraine back in 2014. All of this would add up to less a cold war than a frozen one; a long-term struggle that starts and stops and starts again with no resolution and no greater significance for the rest of the world; a stalemate of varying intensity.

On the other hand, though, Russia has learned enough from the Soviet Union’s mistakes that, even with its diminished geopolitical stature, it’s still more than capable of casting a long shadow over the entire global system; a shadow that warns every assumption we’ve made about the world the last 30 years might soon be obsolete. This is mostly a matter of Russia’s nuclear capabilities giving life to its imperial pretensions, but we shouldn’t overlook the role that its newfound economic resilience has played as well. If nothing else, the decline and fall of the Soviet empire has taught Russia that it can’t afford to weigh its economy down with Marxist dogma, or to hold its development up by alienating key trade partners like China or the Middle East. So it hasn’t anymore. And that’s all it’s taken to give Russia the wherewithal to continue its invasion in the face of punishing Western sanctions that rival the shocks it faced in the 1980s. That said, though, it is true that being cut off from Western supply chains has made it harder for Russia to rearm itself, forcing it, in effect, to replace cannons with cannon fodder, i.e., throwing poorly-trained recruits into battle because it can’t get the parts to produce modern tanks anymore. But the fact remains that even with all this sand thrown in the gears of the Russian war machine, it’s still been able to operate well enough to keep mounting what, at this point, is both a long-lasting and far-reaching challenge to the post-1989 order.

Besides, Russia still has China’s help (and, not long from now, maybe weapons too).

If the Second World War was about democracies allying with left-wing dictatorships to defeat right-wing dictatorships, and the First Cold War was about those same democracies allying with right-win dictatorships to defeat left-wing dictatorships, then this Second Cold War is about democracies on one side taking on dictatorships on the other. Although that’s a bit too optimistic. It turns out there are plenty of democracies—most notably, India, Israel, and Brazil—that are more concerned with maintaining access to Russian oil and weapons than they are with maintaining international borders against Russian depredation. Not to mention the virtual fifth columns, made up of the usual suspects of xenophobes, ideological fellow travelers, and opportunistic mediocrities, who, whether they wear Trump hats or Le Pen pins, want their countries to switch over to Putin’s side. (These aspiring quislings usually couch their support for Russia in terms of their opposition to us spending 0.21 percent of our GDP on military aid to Ukraine, as if this were ruinously expensive rather than being almost a rounding error).

The somewhat surprising conclusion, then, is that winning the First Cold War hasn’t really improved our position in this Second Cold War. The contours of the conflict are even the same: North Atlantic and Pacific Rim democracies arrayed against a Russia-China axis with the rest of the world largely remaining neutral, if only to see which side might be willing to offer them more. Not that there aren’t any differences. Eastern Europe has moved over to our side, the Middle East has drifted towards theirs, and, most important of all, their economies are both much stronger and more intertwined with ours. In a world solely governed by economic self-interest, this kind of mutual dependence would be enough to keep these rivalries from escalating into further hostilities, and it still might. But if it isn’t, it’ll be for two reasons. The first is that merely preparing for the possibility of conflict—say, by banning high-tech exports to China—makes conflict seem more possible by preemptively cutting some of the ties that have bound our economies together. Hard-headed planning risk turning into self-fulfilling prophesy. The second, meanwhile, is China’s potentially combustible mix of a massive economy, a shrinking population, and irredentist dreams of its own. Which is to say that China has the means, motive, but might fear it will lose the opportunity, at least when it comes to its overwhelming manpower advantage, if it waits too much longer to try to take over Taiwan. It’s the same sort of thinking that helped drive Germany to war in 1914, and, notwithstanding that, might actually seem fairly compelling now if Russia is able to show that large-scale conquest is still possible in 2023. That’s why the war in Ukraine feels so existential, less like a battle over borders, and more like the Spanish Civil War: a dress rehearsal for something much darker.

This will be a long war, and long wars are often won—or, more accurately, lost—on the home front. The problem is that might not favor us as much as it used to. By getting Saudi Arabia on its side, Russia has guaranteed that there will be no oil ex machina this time to bring it down from within (although the Wagner mutiny was a bizarre reminder that it still has to worry about unhappy generals). And by cultivating the Trumps of the world, it’s introduced the possibility of our support for Ukraine disappearing at the drop of an election. The question, then, is whether our sanctions will break their economy before their oil price hikes break our politics. It’s the socioeconomic version of trench warfare.

We need a Sputnik moment for manufacturing

That, unfortunately, will be the easy part of this conflict. The hard part will not only be putting together an alliance that can resist Russia and China’s combined military power, but also keeping it together in the face of their inevitable economic inducements. It’s already a struggle. Between Russia’s natural resources and China’s supply chains, there aren’t any countries, not even our own, that can afford to cut themselves off from the Eurasian economy. Even a staunch ally like Japan has felt like it had no choice but to buy Russian oil above the price we’ve tried to cap it at; the rest of our partners have similarly balked at the prospect of banning exports to Russia altogether.

All of this is only more impossible when it comes to China. It’s become the indispensable workshop of the world thanks to its combination of cheap labor, expensive infrastructure, and massive scale, which, by this point, have created such a rich ecosystem of manufacturers and suppliers that it’s hard to even imagine making things anywhere else. The most we’ve been able to do is delude ourselves by shifting some production so we rely a little less on China and rely a little more on countries that rely on China. At the end of the day, though, that changes very little. If anything, China’s manufacturing footprint is still growing: in just the last few years, it’s gone from being a bit player in the global car market to being on the verge of passing Japan as the world’s largest automobile exporter. (Some of that, admittedly, is due to other countries boycotting the Russian market, but the larger part is the result of China’s early lead in electric vehicles). It’s just another reason why everyone from German car executives to the French president and our own Treasury Secretary have, with differing degrees of tact, tried to turn down the temperature on what’s already not cold enough of a war for them. But even the more limited disengagement they have in mind, less a conscious uncoupling than a strategic separation in a few key sectors, will still be too much for us (and our allies) to bear if we don’t markedly increase our own industrial capacity at the same time. We need a Sputnik moment for manufacturing. The Biden administration, to its credit, has already made a substantial down payment on one with its new subsidies for chips and green energy, but we’ll need more, much more, to build back the industrial base we’re going to need.

We were able to win the First Cold War, in no small part, because of the economic strength of our friends and the economic weakness of our foes’ ideas. Neither of those will help us as much this time, though. Not when our oil-rich allies aren’t really allies anymore, and our communist enemies aren’t really communist either. The bad news, then, is that our opponents aren’t going to do us the favor of just collapsing like they did before. But the good news is that this might actually make it easier for us to pressure them ourselves. China needs us, especially with its economy still struggling to beat its post-pandemic blues, just as much as we need them. It’s why their leaders are so worried about our efforts to reduce our dependence on them; enough, in fact, that they’ve finally been willing to restart high-level dialogues with us. They’re not sure how much of a cold war they want when their economy is going through choppy waters and Russia is looking more like an anchor than a buoy. It’s worth emphasizing, though, that even in this more optimistic scenario, where our competition with China is more great game than great war, it is still a competition. We need to be clear-eyed about that. We also have to admit that trading with China isn’t going to make it more democratic, or get it to give up its territorial ambitions. This will be a long-term struggle against a rival who isn’t going to self-destruct; it will require a long-term strategy. One that, first and foremost, builds up our own capacity to try to win what’s no longer a war of ideas, but rather of supply chains.

This one will be harder to win.

Yegor Gaidar, Collapse of an Empire, (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2007), 90-91.

Chris Miller, The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 61.

Gaidar, Collapse of an Empire, 135.

Ibid., 135.

Miller, The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy, 63.

Gaidar, Collapse of an Empire, 97.

Tony Judt, Postwar, (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), 423.

Miller, The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy, 155.

Ibid., 151.

Ibid., 67.

Ibid., 155.

Ibid., 59-60.

Gaidar, Collapse of an Empire, 176-77.

Miller, The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy, 160.

Ibid., 148.

Steve Hanke and Nicholas Krus, “World Hyperinflations,” Cato Working Paper no. 8 (2012): 12-14. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/workingpaper-8_1.pdf.